A Pause for Art and Empathy

The de Saisset showcases artist Bryan Ida’s con.Text show, exhibiting a powerful message of connectedness under political strife

In the laborious task of completing his pieces Grandmother and Grandfather, artist Bryan Ida used both hands to write out the entirety of Executive Order 9066, which established Japanese internment camps, in the shape of a man – weary and surrounded with luggage.

Grandfather depicts Ida’s own kin as he awaits a bus that will relocate him to an internment camp. The portrait is entirely composed of those words that condemned so many to captivity, overlapped and interlaced to create shadow and shape.

The original photo was taken by Dorthea Lange in a series commissioned to chronicle the internment of Japanese Americans. Ida’s family had been unaware of this photo until they saw them, by chance, on display at an exhibit of the photographer’s work. Ida later discovered the photo of his grandmother when looking through Lange’s archives.

Grandmother and Grandfather are cornerstone pieces of Ida’s con.Text series. The collection of eighteen portraits is currently on display at the de Saisset Museum.

The exhibit showcases 18 portraits from the series. Ida uses iconic political texts and government documents as his medium, the words woven together in his handwriting to warp and rework their initial meaning. He rejects the idea that these words define the subject, instead bleeding the subjects’ identity.

“What's really beautiful about the work is that these words matter,” said Chris Sicat, exhibitions project coordinator at the de Saisset Museum. “These portraits are not necessarily defined by those policies or statements, but they become a testament to their resilience and their beauty.”

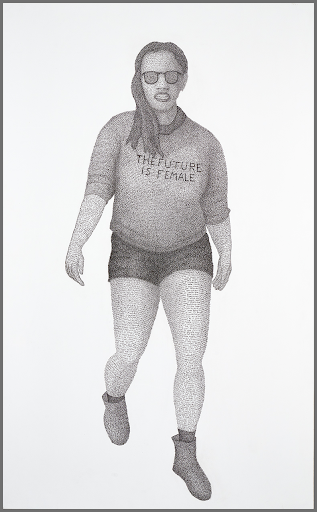

Composed of the text of the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments, a document drafted at the first woman-organized women's rights convention, Ida’s piece Protestor displays a woman proudly and powerfully marching in a protest that arose post-2016 election.

Sicat sees the subjects’ poses as exemplifying their strength – be that with or against the force of the words used to depict them.

“The ‘Future is Female’ piece is one where you see the policies, testaments and sentiment,” he said, referencing Protestor. “That pose, and The Neighbor piece as well, says: We are here.”

The Neighbor is constructed from Trump’s controversial social media statements amid his early-presidency enaction of anti-Muslim immigration policies.

“I thought of it when Donald Trump was trying to justify the enactment of a Muslim ban on Twitter,” Ida reflected. “He was tweeting a lot and I thought of the idea to use the words of his tweets to render a portrait of my neighbor, who is Muslim. I saw her going to the temple on a Saturday morning wearing a full niqab and I wanted to use her as a subject.”

The Neighbor was the first piece Ida completed in the con.Text series, and it inspired his decision to continue using texts as a medium for portraiture – a step in a new direction for the artist’s style.

“When the elections of 2016 were in their full fight, I felt the need to switch to something that expressed the zeitgeist of the moment,” Ida said.

The portraits in con.Text all depict people he has encountered or has a relationship with.

“These are not strangers he went looking for that were affected by these policies; these are his neighbors, his friends and his family members,” Sicat said. “It's very powerful that every one of us has a very rich experience of how policies, laws or statements – official or social – affect us. The exhibit is a reminder that every one of us here walking on campus have our own stories, our own words that we carry with us.”

For Lauren Baines, interim director at de Saisset, the broad effects of these policies and the experience of carrying their weight is what makes the series linger in viewers’ minds. Baines noted that while some of the texts Ida uses as his medium are painful and challenging, it is important to see how the power structures that continue to harm our community were created.

“Sometimes we feel disconnected from policy and government, and sometimes we want to distance ourselves from what's happening in that arena,” Baines said. “But the amount that we can see entire communities, generations and our friends and family today connected by words that one person or a small group wrote on a document centuries ago calls us to engage or re-engage, rather than to distance.”

The exhibit, which will run the remainder of the academic year, offers students and visitors an opportunity to re-engage. De Saisset’s Gallery 3 holds a reflection area that allows visitors to read through the policies that Ida utilizes in his pieces. Visitors can also respond to prompts on note cards as well as others’ notes, in turn creating the dialogue that this series spurs.

“Engagement is something that's really important,” said Sicat. “It’s vital to coming out of this. Policy does affect you. It affects your neighbors. It affects your family members. It affects your community.”

“I hope it provides a moment for everyone to come pause for empathy, and that this may move us forward. These are words and portraitures that we all can see ourselves in.”