How a Global Pandemic Became a Beacon of Hope for San Francisco’s Homelessness Crisis

Despite a growing rate of homelessness throughout SF, new funds allocated to the city as part of the nation-wide COVID-19 relief plan offer promise to solve the century-old problem.

Walking through the Tenderloin, one of the city's oldest and most infamous neighborhoods, has begun to feel like “experiencing a refugee camp,” said Ed Dilworth, a long-time San Francisco resident. Certain areas are worse off than others, but almost any local would agree that the city’s homelessness crisis has gotten out of hand.

As housing prices continued to rise at the start of the 21st century, and the city’s federal funding drastically declined, many were forced out of their homes and onto the streets.

“If people can’t afford to pay rent, some have no option but to go without a home,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, director of the San Francisco branch for the Coalition for the Homeless.

It’s important to note the difference between homelessness as a result of housing instability (those who have become unable to afford rent) and chronic homelessness (typically driven by drug addiction, poverty and mental illness). While separate but equally problematic, both have drastically impacted the infrastructure and culture of San Francisco.

Housing prices have especially become an issue in recent years. The economics and research team at Zillow analyzed that, “once cities cross a threshold where the typical resident must spend more than a third of their income on housing, homelessness begins to spike rapidly.”

This creates a ripple effect, enabling high-income residents to rent typically middle-income housing, and middle-income residents to rent traditionally low-income housing. The result is a large population of low-income residents with nowhere to live.

“It's sort of a game of musical chairs,” said National Alliance to End Homelessness president, Nan Roman. “People who have already have a strike against them — because they have mental illness or a substance abuse disorder or a disability — are the least likely to get the chair."

In some cases, these disabilities hinder homeless individuals from wanting to change their situation.

“Because they’ve been living without shelter for so long, and have created their own ‘neighborhoods’ physically on the streets...they start to normalize their living situation and because of their illness, resist support,” said Karyn Connell, a faculty member at Santa Clara University.

According to the most recent city-conducted biennial report released in January 2019, there were over 8,035 individuals reported to be homeless, 5,180 of whom remain unsheltered. This is a more than 14% increase from the 2017 numbers collected by the county.

Out of every 100,000 city residents, 882 are reported to be homeless, which is notably higher than averages released by cities with relatively similar sizes.

42% of these homeless individuals are reported to be in emergency, transitional, and stabilization homes, according to the 2017 PIT count report. Again, when evaluating these numbers in relation to comparable cities, the percentage is startling.

San Francisco has the funding ($300 million dollars per year of it) to account for this issue, but somehow it continues to flounder.

While the pandemic has brought about an unprecedented number of new challenges for residents and homeless populations, COVID-19 federal relief funds hold promise for a long-awaited success story.

In response to the over $35 million increase in general fund support, primarily from one-time COVID-19 assistance from the HSH FY20-21 budget, S.F. Mayor, London Breed announced her new Homelessness Recovery Plan. This is a project composed of new programs to “decrease homelessness in San Francisco and recover from the pandemic,” Breed said in her July 2020 address.

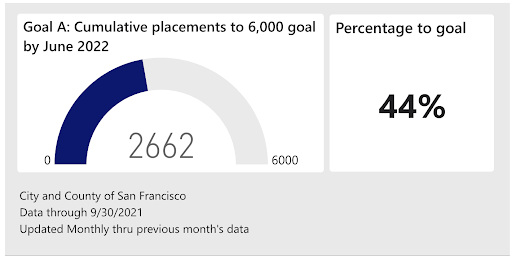

The Homelessness Recovery Plan will not only create 6,000 new placements in local shelters, but will include an additional 4,500 beds in permanent supportive housing for youth, families, and adults over the next two years.

It’s structured on three central premises, according to Breed. Firstly, it seeks to expand housing options for homeless individuals. Then, the implementation of new shelters, navigation centers, and other forms of alternative housing. Once this is complete, Breed believes the city can begin making healthcare, employment, and other housing resources more accessible to vulnerable populations.

“Ultimately, housing is the solution to homelessness,” Breed said in a September 2020 public statement. “By expanding access to housing and other support, we can create real opportunities for people to get off the streets and create a path for them to live a fuller, healthier life,” she said.

Breed’s initiative also ensures additional placements are provided in these shelters for individuals who relocated to Shelter in Place hotels during the pandemic. Ideally, as the city emerges from COVID-19, these residents can continue to have housing and not go back to living on the streets.

“This plan is nothing short of a game changer,” said Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing interim director, Abigail Stewart-Kahn, in a July 2020 press release. “San Francisco leads in the most permanent supportive housing per capita of any community in the country and with the Mayor’s leadership, will have the largest one-time expansion of housing in 20 years.”

Funding for the plan has become largely dependent on the increase in federal, state and local funds generated from the city’s FY20-21 budget, in addition to Project Homekey, which awarded the city with $45 million to purchase the Granada Hotel to serve as the newest housing center in San Francisco.

Additional FEMA reimbursements, Proposition C support and money from the Health and Recovery General Obligation Bond have allowed for greater shelter expansion efforts. The FY21‐23 HSH Budget details this and credits the one-time $400 million investment as being a pivotal factor for success.

San Francisco has continued to track its progress in executing the two-year plan, which will conclude in July 2022, and so far has been largely successful in their performance efforts.

As of September, the city reported reaching 44% of its goal in housing 6,000 more homeless individuals. It also reported being nearly half-way toward adding 1,500 new permanent housing units.

San Francisco has also dedicated funding to provide 24 month support for rent payments, as well as short-term compensation for eviction prevention and grant funding for missed rent checks.

Perhaps the most impactful undertaking in the last year has been the construction and opening of the city’s latest Navigation Center - an advanced housing unit providing support and resources all in one place.

Located at 1925 Evans St., the Bayview SAFE Navigation Center is the tenth Navigation Center to open its doors. As of January, it has housed 116 residents, increasing the total occupancy at these Navigation Centers to more than 14,000 on any given night.

“The pandemic has given us the opportunity to fully realize the Mayor’s Homelessness Recovery Plan,” said HSH Public Information Officer, Denny Machuca-Grebe. The funding provided in the last year gave us the ability to execute the largest expansion in housing in over 20 years. I can’t imagine that this kind of undertaking could have been done without COVID-19 relief,” he said.

With an upcoming fiscal budget leveraging over $1.2 billion for the next two years, the HSH, the Mayor’s office, and many other impacted city residents seem more optimistic about ending widespread homelessness than they have in a long time.

“I do think that COVID taught us a lot about what we can do and what we can fund and how that makes a difference,” Shireen McSpadden, director of the HSH, said in a recent interview. “And so, I think to that end, we'll keep the sense of urgency as well.”