In Defense of Philosophy

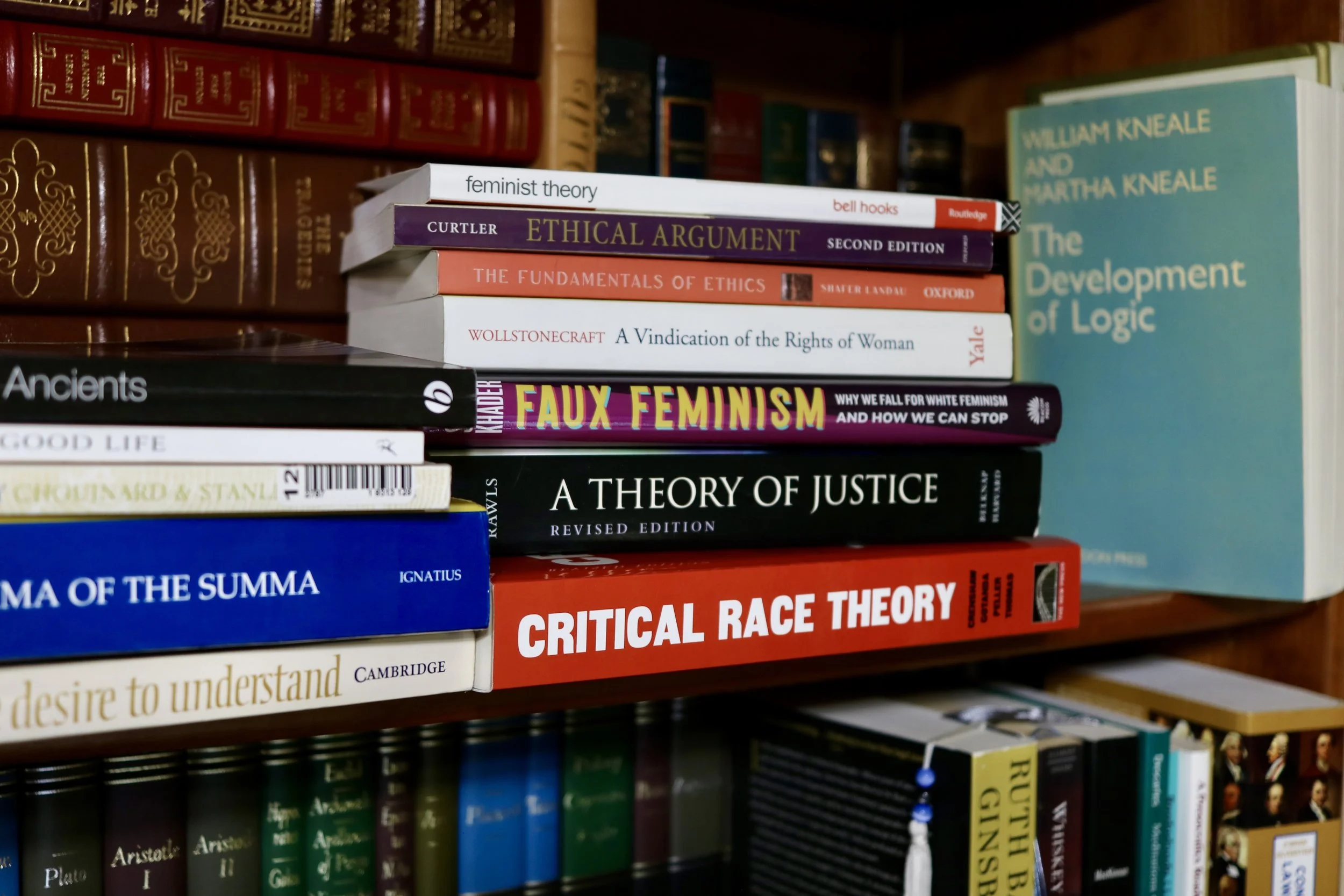

Photo by Keith H. Dinh for The Santa Clara

It is rare that an opinion piece elicits such a deep sense of dismay in me, but Katherine Ioffe’s ’26 recent article, “Philosophy Sucks,” did just that—and it demands a response. As an accounting major with both a philosophy minor and the applied ethics Pathway, I find her dismissal of philosophical inquiry both concerning and misguided. Philosophy has been a source of joy and intellectual growth in my life. It has challenged my biases, sharpened my reasoning and enriched my understanding of the world. To dismiss it as redundant or nonsensical, as Ioffe does, is not only disheartening but also misguided.

Let’s address the heart of her critique: the idea that philosophy is a never-ending discussion of questions with no answers. True, philosophy resists simple, definitive conclusions. But this is not a bug, it is a feature. The world is complex, and so are the ethical, moral and existential dilemmas we face. Ioffe derides the famous trolley problem as “high-falutin” and irrelevant. Yet, the spirit of this thought experiment is alive in real-world issues: self-driving cars deciding which lives to prioritize in an accident, debates over abortion and the death penalty or how society should address reparations for historical injustices. These are not hypothetical; they are pressing ethical challenges that demand philosophical care.

The dismissal of philosophical exercises as pointless also misses the point of these exercises. They are not meant to provide definitive answers, but to develop critical thinking skills and moral reasoning. When we debate whether lying is wrong, we are not merely playing with abstract ideas. We are preparing ourselves for real-life situations: Should you tell the truth to a gunman asking for your friend’s location? Should a whistleblower reveal company secrets to expose corruption at the cost of their career and livelihood?

Ioffe also suggests morality is innate, learned “by example” and that ethical training cannot “make anyone ethical.” While it is true that morality starts in the heart, this does not mean that ethical education is futile. As Socrates famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Philosophy is that examination—a process of questioning, analyzing and striving to understand what it means to live a good life.

Ioffe’s claim that the answers to life’s biggest questions “don’t sit inside a book” but “in the human person themselves” is, ironically, a deeply philosophical statement. Moreover, the suggestion that we can simply “know” that murder, lying or stealing is wrong ignores the complexities of real-world ethics.

Is murder wrong if it prevents genocide?

Is lying wrong if it saves lives?

Is stealing wrong if it is the only way to feed a starving family?

These are not trivial questions. They require us to weigh competing values, consider context and make difficult choices with prudence. Philosophy trains us to approach such dilemmas with intellectual rigor and moral sensitivity.

While I respect Ioffe’s opinion, her conclusion misses the true value of philosophy. Philosophy does not suck. Philosophy challenges, it provokes and yes, oftentimes, it frustrates. But it also enlightens, inspires and empowers. It helps us make sense of the world and our place within it.

In a world fraught with ethical dilemmas and moral failings—such as systemic injustices, accounting scandals, the ongoing battles for women’s reproductive rights, transgender rights or fair pay at universities—philosophy provides a vital framework for navigating these complexities. It compels us to grapple with questions arising from advancing technologies, the morality of war and growing inequality.

Now more than ever, the need for careful philosophical inquiry is undeniable.