Intersecting Threads

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

John Redinbo: Did you always work with textiles or did you work your way towards that as you explored art?

Kira Hultgren: I think I mostly worked with structure, like the woven structure, even when I was really young. I loved tracing patterns and lines, just out in the world.

I started weaving pretty young, just kind of playing around on little looms, then doing a lot of sewing and quilting, sewing clothes, that kind of thing all through childhood. “She's very crafty.” That’s how I was described growing up.

My dad's family is from Mexico and my mom's Family is from India, but I mostly spent summers growing up in the U.S. and in Vancouver, Canada, (because that's where all my Indian family is) and in L.A. where my parents were raised. But then there were a couple of summers when we went to Mexico. For my Dad especially, it was important that my brother and I kind of had a sense of where we came from. I latched on to the culture of it.

There's a way that people are expressing themselves that isn't what I see in the States. There’s that first experience of, “Oh, the people who are respected and revered in these communities are weavers and they're pottery makers and ceramicists.” So I started spending as much time as I could with artists, especially with weavers.

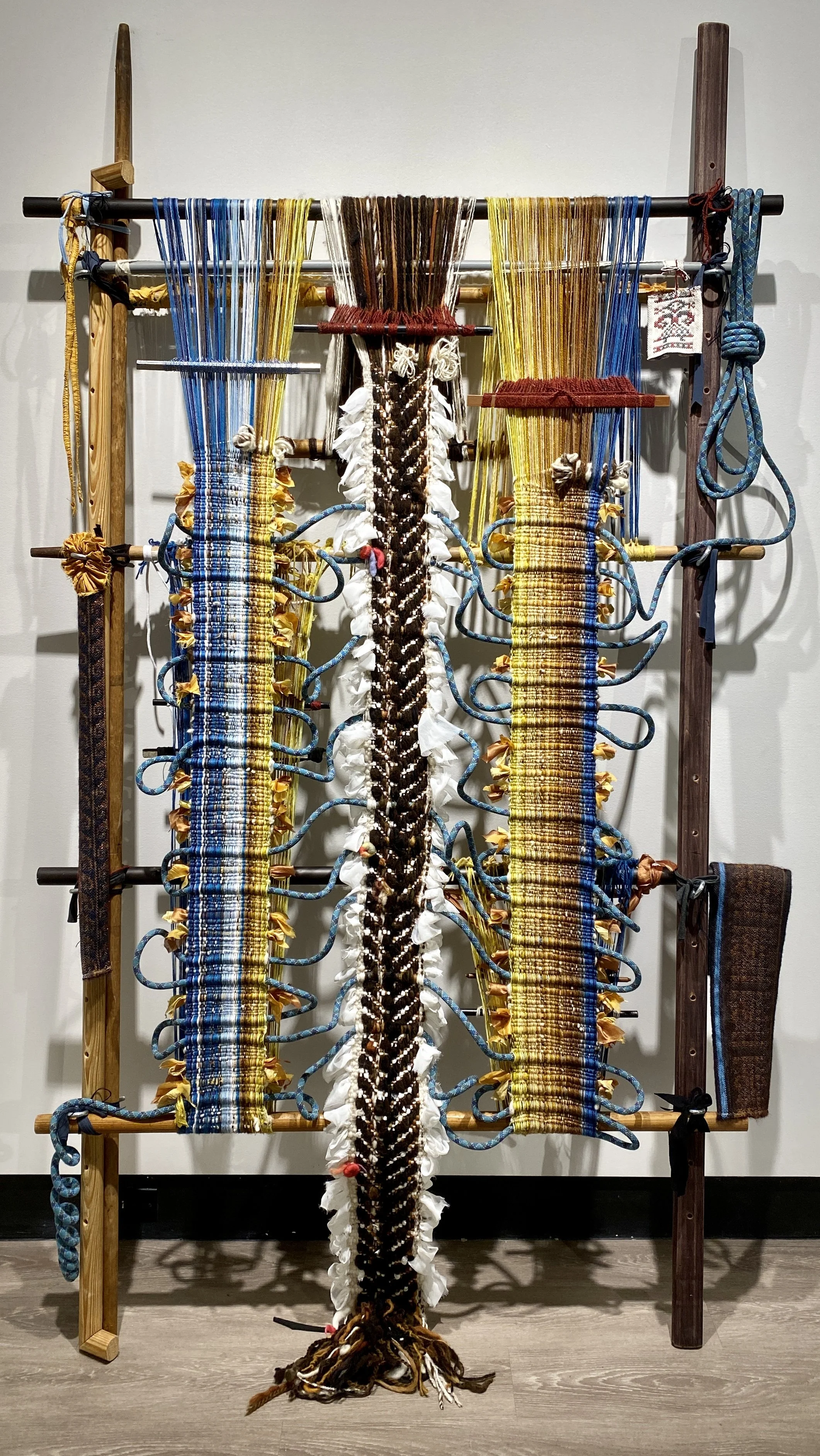

Hultgren’s piece Split From Center. Photo by Elena Peng

Do you think your passion for history and storytelling first emerged from that exploration of your heritage?

I think it came from growing up having dinner table conversations with my parents, hearing them negotiate their own position in the U.S. Because they're both first generation. I'm second generation and hearing them say, “This is all new to us. We're really making it up as we go along in the sense of both what it means to be American, but also what it means to raise American children.”

It was hearing stories about places and contexts and experiences that I didn’t encounter.

Is that also where the ability to reflect as an artist arose from?

Yeah, I think that's why weaving for me makes so much sense. Intuitively, a lot of the cloth structure expresses that tension or that confusion. I'm always gathering material, and the material is sometimes language and stories.

I'm weaving in my life, metaphorically, like, “What does it mean to live with these stories, but also have my experience,in tension with another?”

And then having outside influences, creating this cloth of what makes sense. I always felt like the single narrative–my story–was always contingent on twenty other stories to position me at this. It gave me permission in some ways to step back and say, “All right, here's the material. How do I fit it together as a studio practice rather than something I'm going through in my body and just trying to survive? That was my experience.

Hufgren’s In the Silence Between Mother Tongues. Photo by Elena Peng

At what point did you turn the craft into your main focus?

In Argentina, that's where I was like, “Oh, like I'm hearing all these stories, it's actually kind of similar.” We were in Patagonia, in super Southern Argentina. I fell in with these Mapuche Argentine weavers who had a government-sponsored collective where they were tasked with cultural reclamation in the area. To encourage this next generation who's all leaving the area and going to the major cities to try to keep that Mapuche cultural heritage.

I was interviewing them and as I was talking, they said, “Well, you're not gonna just sit here and talk to us. You know how to do this stuff. Spin yarn for us while we're talking, or dye material while we're talking. Wash and clean the wool. Okay, now you've learned all of this, you need to know how to weave.”

And they were like, “Well, for us, it's really important for you to be able to take this story out into the world. If it's going through you, that's the same way it's going through us. Now you're telling our story as you tell your story.”

For them, at least my mentor, Mari, she was like, “Material, textiles, hold the multiple stories better than anything else. Just tell the story however it's going to come out.”

It was like, “Oh. What they're doing is really similar to what they're doing in Mexico.” Totally different. Visually, it looks like a different structure, but mechanically it's actually pretty similar.

It wasn't like I walked in and knew nothing. I had this background knowledge that was activated in a really critical way. Suddenly I realized, “Oh, now all this post-colonial stuff that I was reading and everything that I was doing suddenly finds its way of expressing itself in this experience, living in Argentina.”

So what does that look like in the U.S.? It's the foraging, the urban wild foraging. It's electrical cables. A renewable resource of the U. S. is our trash. So let's use that. I can tell the story that way.

Hufren’s To Carry Every Weight but Your Own. Photo by Elena Peng

Do you think when you initially entered arts academia, it was a world that rewarded that multicultural approach to your work? Or do you think that's a path you had to forge for yourself?

I think the answer is a little bit of both. There were a couple of really key textile books that were coming out in the mid-2000s.

Elissa Auther wrote “String, Felt, Thread.” In contemporary art, there's this whole genre of what's called women's work. It's not the way that I came to textiles, but it's the way textiles came to contemporary art. Auther said any kind of material expression is marginalized in contemporary art. So it's sculpture, then it goes to textiles and then any performance. All of that is severely discounted as: “is it really fine art anymore?”

In some ways, I was having a very similar conversation in both spaces of exception, like sort of everyone is tacitly agreeing that we want all kinds of diversity in both media as well as race and ethnicity. But it feels like, maybe it’s just representation? Do we want different kinds of faces in the room and experiences? Or is it actually changing the conversation and challenging and allowing?

It's not like I came out of nowhere sort of thing. The sort of feeling up until 2016 was, “We're post-gender, we're post-race now. We're post even discipline, everything's interdisciplinary. We don't even have to think about that. We figured it out.”

But then Trump was elected and it was like, “Oh, wait a second. There's a lot of racism and a lot of sexism and all of this stuff that's still very present.” And so how do textiles, women's work, fit in? Women's work that's complicated by the labor movement in the U.S.

There's a lot of domestic labor from Mexican women working here. That's my dad's side of the family story. It feels like maybe the U.S. is ready to hear not just representational stories, but artists asking the questions and calling out the histories that we can't learn in the classroom; that we've never been able to learn.

I'm contributing to, hopefully, this idea of the U. S. being ready to hear stories that are not part of our curriculum, that are going to be. Because now everyone's talking about them.

What would you say is the Common Thread, not only in your work, but related to the other artists currently featured in the exhibit?

Marianne McGrath is the curator of “Common Threads.” She picked the pieces. So a lot of this was her asking what work was available at the time the show was going to happen. So I sent her a portfolio of work. The thing I really like about this show is it has “In the Silence Between Mother Tongues” and “Split from Center.” Those two were made at very different moments for very different contexts. To have them in the same space together is awesome.

Then, the idea of the scaffold. Or what it means to scaffold stories, to have material that's like the loom, or maybe the sculpt or maybe it's the work itself that's kind of like supporting. It gives the framework to support and build the story. The scaffold happened with “In the Silence Between Mother Tongues.”

Then I took that idea of scaffolding, building off of Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa’s work, “The Bridge Called Her Back.” It’s this seminal work in Chicano literature of what it means to stretch across the Rio Grande and have your body be the scaffolding or support for the way that a lot of the U.S. (and this is in the 80s and 90s) was trying to understand intersectional identity.

The Common Threads exhibit features textile artists. Video by Reece Chapman

Your bio said that your work uses “weaving as a performative critique of the visual.”

When I was at California College of the Arts, I did a visual and critical studies degree. Critical studies usually looks at writing and visuals.

There's also material critical studies–the way that material will totally change the way that someone looks at or feels something. That was where my weaving became almost a critique of the visual; that what you're seeing on the surface of the weaving–the colors, the composition–is only the surface. There's also the structure that makes the visual. And there's the context, ideally, that's holding up this piece that's being activated through the loom or the skeleton. All of this weaving becomes this critique of what we're seeing just as a surface image.

There was this automatic assumption of, because of how I look, that I must have grown up doing this. Like, “is your family weavers? Are you a Navajo weaver?” And it's like, “No, but I get why you're saying that, because that's our context with indigenous kinds of weaving in the U.S. It's largely coming out of Navajo weaving.”

It's mostly this National Geographic image in our heads of the “woman at the loom.” So when I'm then coming into today's context in a contemporary art sense of weaving, it's going to be different than the textile conversations Elissa Auther was talking about. In the 50s, 60s and 70s, it was largely middle-to-upper class white women weaving. That provokes a different type of conversation, compared to my work.

It’s also performing an identity, performing these kinds of assumptions. That's where this critique of the visual comes in, where it's both because I'm doing it and it's weaving.

But it's also this: weaving is always more than just the visual.